Stop Struggling with Recruitment: High-Efficiency Food Machinery for Labor-Depleted Production Lines

In-Depth Analysis: Practical Automation Strategies for Food Manufacturers Facing Labor Shortages|ProductionGuide

09 Jan, 2026Labor Shortages Are Structural, Not Temporary. Between 2024 and 2025, the ANKO team has seen a sharp increase in inquiries related to labor management challenges. This is no longer a regional issue—it is a global structural problem affecting food factories and chain foodservice operators alike. According to 《Richter’s 2025 Food Sector Study》, confidence in the U.S. food labor market dropped to 46%, doubling the decline from the previous year. The 《OECD Employment Outlook 2025》 further highlights mounting pressure in aging economies such as Japan, South Korea, Italy, and Bulgaria, driven by demographic shifts and labor policies. However, ANKO’s field experience indicates that labor is only part of the problem.

Production Stability Is the Real Priority—and Labor Is Only One Variable

A leading restaurant chain in the Philippines shared a critical insight:“Hiring and retention have been long-term issues, but the real risk lies in the stability of key operators. When core staff changes, the entire production line must be adjusted. Even with stable orders and sufficient raw materials, delivery schedules become unpredictable.”

In an environment shaped by inflation, labor shortages, and volatile demand, food manufacturers are confronting a hard truth: The labor shortage is no longer a temporary phenomenon but rather a long-term structural risk. Production lines that rely heavily on skilled workers are highly vulnerable—absence or transition can slow or halt output entirely.

Labor Risk: A Crisis That Forces Strategic Change

Labor shortages are often underestimated. In the short term, they appear manageable through overtime and rescheduling. Over time, however, they evolve into systemic production risk. When output stability depends on specific individuals, manufacturers lose the ability to commit to delivery timelines, pricing, and order flexibility. As one operator noted:“During peak season, it’s not that we don’t want orders—we can’t guarantee delivery.”

This erosion does not immediately appear in revenue figures, but it steadily weakens brand credibility and customer retention. For small and mid-sized food factories, this is the most dangerous position: too large to rely on manual labor, yet too constrained to absorb a full-scale automation overhaul.

Why Fully Integrated Automation Often Fails in Food Manufacturing

Under labor pressure, full automation appears to be the fastest solution. In practice, it is often the riskiest. A complete production line upgrade requires not only capital investment in food automation equipment, but also synchronized changes in workflow design, management systems, and workforce capability.

When any one of these elements falls behind, equipment utilization drops sharply and automation becomes an operational burden rather than an advantage. Most failed projects are not caused by machine performance, but by a mismatch between investment pace and operational readiness. Successful automation depends on one key question: Can labor dependency be reduced without disrupting current production commitments?

A French Case Study: When Automation Moves Faster Than Operations

A French frozen food manufacturer supplying local supermarkets faced this exact challenge. After investing heavily in equipment years earlier, they encountered persistent bottlenecks and turned to ANKO for a full production reassessment.

The plant manager admitted:“Automation itself wasn’t the problem. We tried to do everything at once. The machines arrived quickly, but our processes and people couldn’t keep up. We spent heavily, yet production slowed instead of improving.”

If Automation Has a Sequence, Where Should It Start?

Equipment installation, layout changes, and workflow adjustments all carry operational risk. A viable food production line planning strategy must therefore be phased and problem-focused. The first priority should be processes that are highly dependent on skilled labor, difficult to train consistently, and least tolerant of operational errors.

Automation should initially run in parallel with labor, not as an immediate replacement. While this approach may not deliver instant capacity growth, it significantly improves production stability and reduces reliance on key personnel.

Why Forming Is Usually the First Automation Step

For most mid-sized food factories, the immediate goal is not maximum output—it is stable delivery. In this phase, automation should stabilize the most fragile process. Forming is typically the first critical node. It sets the pace for the entire production line; any fluctuation cascades downstream. The value of investment at this stage is not speed, but consistency—ensuring stable operation even with fewer workers, temporary absences, or staff rotation.

From Stability to Scale: Reducing Physical Labor Load

Once core processes can withstand labor volatility, manufacturers face seasonal peaks and high turnover. At this stage, automation shifts toward reducing physical workload, particularly in repetitive, labor-intensive preparation processes.

While these systems may not immediately boost output, they improve retention, reduce injury risk, and ensure baseline operability during labor shortages.

Why Automation Gaps Are Most Visible at the Forming Stage

Taking dumpling production as an example: At 10,000 pieces per hour, manual production typically requires around 12 experienced workers. Output, quality, and consistency are highly dependent on individual performance—excluding additional labor for preparation. With a forming machine, the same capacity can be achieved with just two operators, once materials are prepared. Each unit is uniform in weight, shape, and quality, making production predictable, manageable, and easier to control. The true shift is not labor reduction alone, but the elimination of structural dependence on highly skilled operators.

As product complexity increases, the gap widens further. For Lacha Paratha, which involves repeated sheeting, layering, and heavy handling, manual production requires sustained physical labor and carries high injury and turnover risk. With automation, stable production can be maintained with approximately ten operators, significantly lowering operational risk and management cost. (Lacha Paratha Case Studies)

According to ANKO’s European sales team, the market signal is clear: food manufacturers that fail to stabilize their core processes within two years will struggle to scale production, secure new customers, or launch new products. The real risk is not outdated equipment, but production lines that are overly dependent on specific individuals with no viable backup.

Stabilize First—Only Then Does Expansion Make Sense

Scaling capacity only delivers value once upstream processes are stable and production rhythm is predictable. At that point, downstream automation—such as tray arranging, packaging, freezing, and quality inspection—can fully realize their benefits in consistency and error reduction. This phase typically applies to mid-to-large food factories with higher output volumes and stricter requirements for storage, logistics, and delivery reliability.

Only after structural stability is achieved should companies evaluate advanced automation and IoT-based process optimization. These systems demand higher investment and operational maturity. Their purpose is no longer to solve labor shortages, but to improve decision-making efficiency and long-term competitiveness.

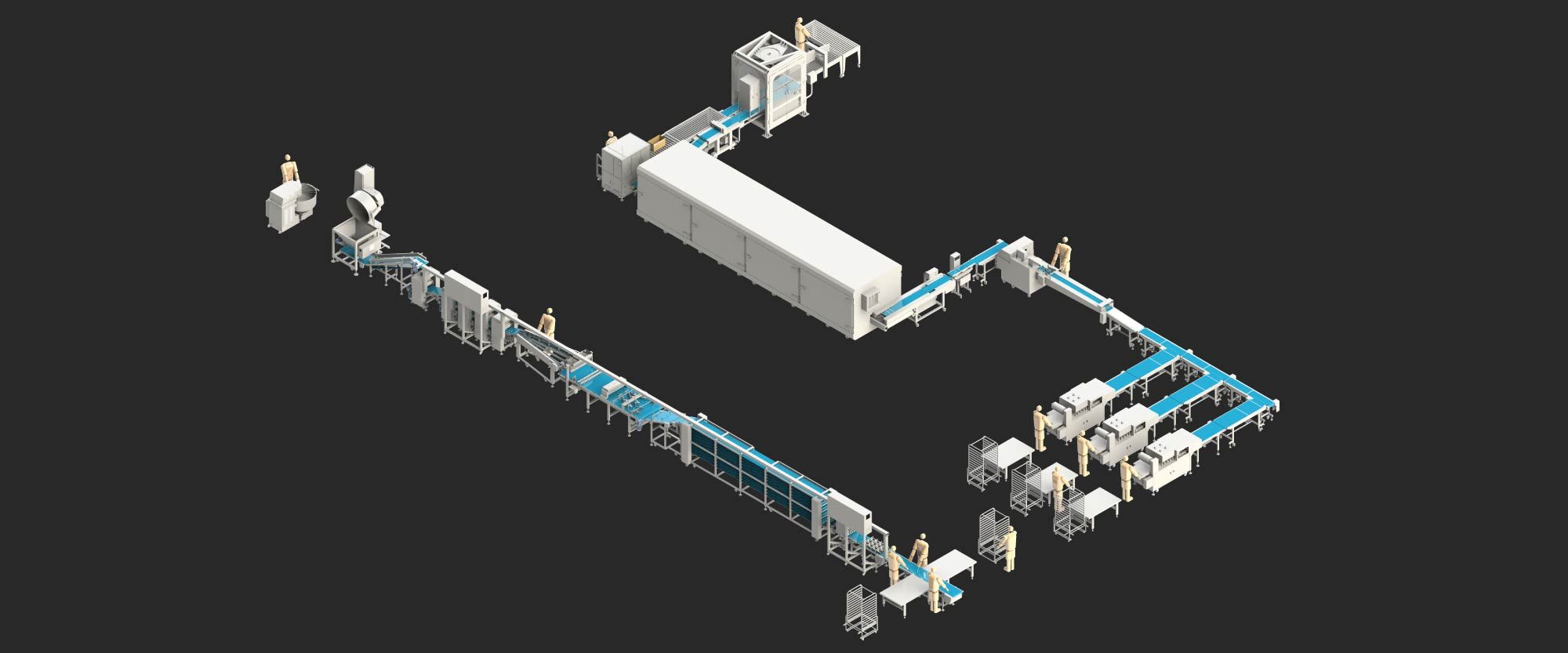

What Food Manufacturers Really Need: A Partner, Not Just a Machine Supplier

ANKO General Manager Richard Ouyang:“Successful automation is never about doing everything at once. It starts with the first step that cannot fail. Our role is to bridge the gap between equipment and real production conditions. Because food manufacturing is inherently complex, we design modular machinery that allows customers to build production lines progressively—like assembling a puzzle—while keeping automation investment controlled and scalable.”

This is the role a food machinery supplier must play today: not just delivering equipment, but helping manufacturers make resilient production decisions in an uncertain operating environment.

Source: Richter’s 2025 Food Sector Study、 OECD Employment Outlook 2025